In 1826, French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce achieved something never done before: he fixed an image permanently using light. His photograph, “Point de vue du Gras”, is the earliest surviving photograph in history. Before then, images produced by light-sensitive materials would fade when exposed to light. Niépce’s breakthrough process, which he called a “Heliograph”, changed that forever, and marks the birth of photography.

200 years later, Niépce’s original heliograph still survives and is now preserved at the University of Texas. Interestingly, the word “photograph” did not yet exist. That term wasn’t be used until 1839 by English scientist John Herschel.

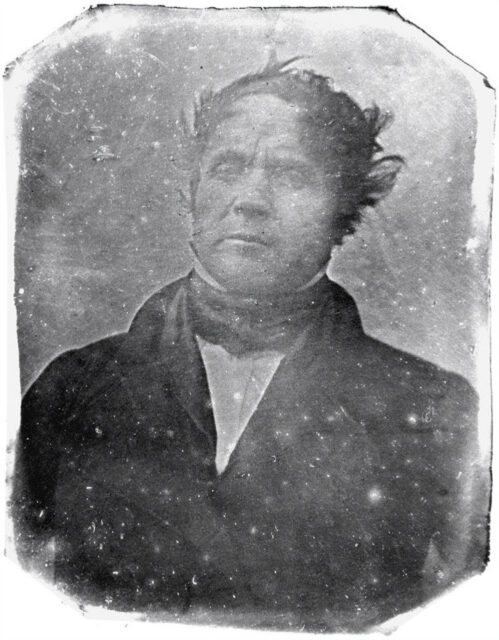

Niépce passed away in 1833, but his work lived on through his business partner, Louis Daguerre. Daguerre continued refining image-making techniques and eventually developed the Daguerreotype. Unlike Niépce’s heliograph, which required exposure times measured in hours, the Daguerreotype needed only minutes to capture a latent image. This reduction made portrait photography possible for the first time.

Because each Daguerreotype was a unique, one-off image, it could not be reproduced but it could depict people. A portrait of Constant Huet from 1837, attributed to Daguerre, is considered the oldest known photograph of a person.

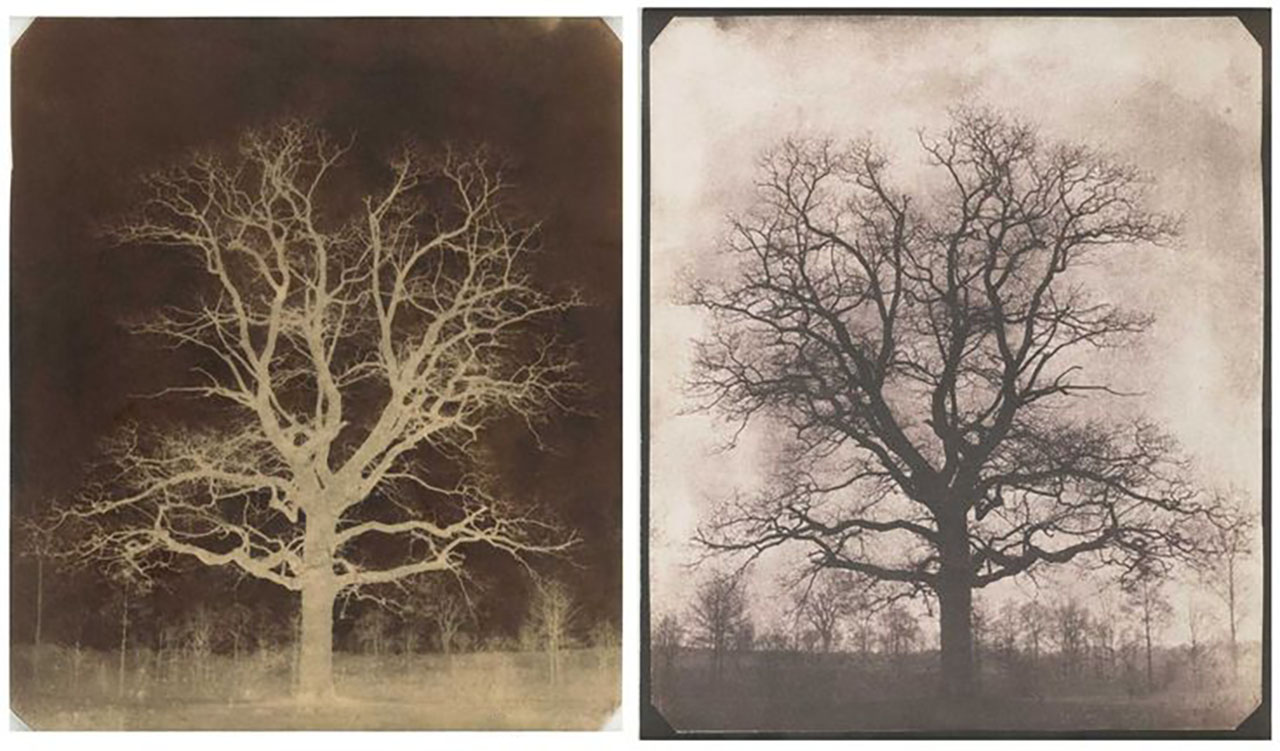

While Daguerre was working in France, photography was also evolving independently in England. Henry Fox Talbot developed the Talbotype process, which introduced a revolutionary idea: the photographic negative. By placing a negative in contact with another sheet of sensitised paper, photographers could create multiple copies of a single image. This concept, reproducibility, became foundational to photography’s future.

Over the next 150 years, contact printing and photographic materials evolved steadily, moving from paper negatives to glass plates and eventually to flexible celluloid film. Each step improved image quality, durability, and ease of use.

A major turning point came in 1888 when George Eastman released the Kodak No. 1 camera. Eastman didn’t just sell a camera, he sold a system. Customers would take 100 photographs, send the entire camera back to Kodak, and receive their developed prints along with the reloaded camera. Photography was no longer reserved for scientists or professionals; it was becoming accessible to the public.

Kodak went on to define photography throughout much of the 20th century. In 1935, the company introduced Kodachrome, bringing high-quality colour photography into the mainstream.

Another milestone arrived in 1925 with the introduction of the Leica I camera. Designed by Oskar Barnack, the Leica used 35mm film originally developed for motion pictures. While movie film used a 16×22mm frame, Barnack doubled it to 24×36mm, creating a format ideal for still photography. This 35mm standard became so influential that it later defined the “full-frame” sensor size dominates modern digital cameras today.

Digital photography began gaining traction in the early 2000s, driven by advancements in image sensors such as CCDs, efficient file formats like JPEG, and the rapid growth of the Internet. Together, these technologies met a growing desire for instant image capture and sharing. The 2000 Sydney Olympics marked a symbolic moment for digital photography, with photographers widely using the Nikon D1, the first truly affordable professional digital SLR.

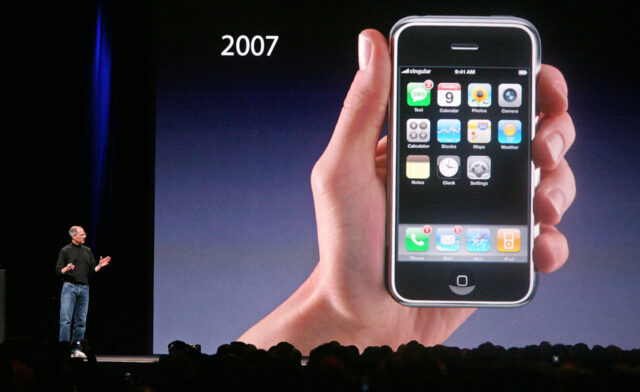

Then, in 2007, Steve Jobs stepped onto the stage at Macworld and unveiled the Apple iPhone. While initially dismissed by many as a phone with a novelty camera, the iPhone, and smartphones that followed, quickly replaced compact cameras for the general public. Photography became something everyone carried in their pocket.

Today, in the 21st century, Apple dominates the photographic world. Two centuries after Niépce first captured a permanent image on a pewter plate, photography continues to blend art and science.